Amid all the debates about how AI affects jobs, science, the environment, and everything else, there’s a question of how large language models impact the people using them directly.

A new study from the MIT Media Lab implies that using AI tools reduces brain activity in some ways, which is understandably alarming. But I think that’s only part of the story. How we use AI, like any other piece of technology, is what really matters.

Here’s what the researchers did to test AI’s effect on the brain: They asked 54 students to write essays using one of three methods: their own brains, a search engine, or an AI assistant, specifically ChatGPT.

Over three sessions, the students stuck with their assigned tools. Then they swapped, with the AI users going tool-free, and the non-tool users employing AI.

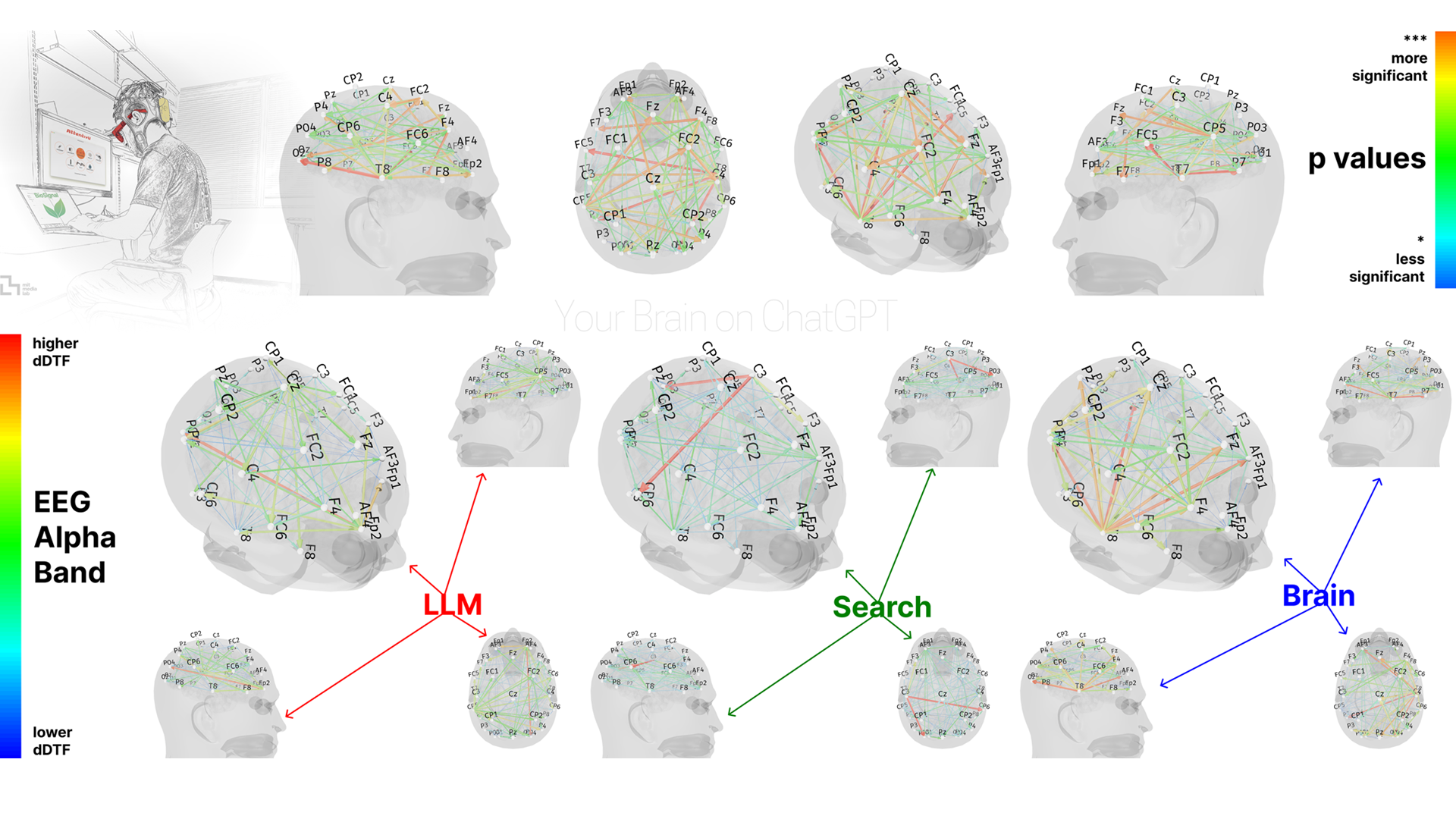

EEG headsets measured their brain activity throughout, and a group of humans, plus a specially trained AI, scored the resulting essays. Researchers also interviewed each student about their experience.

As you might expect, the group relying on their brains showed the most engagement, best memory, and the most sense of ownership over their work, as evidenced by how much they could quote from them.

The ones using AI at first had less impressive recall and brain connectivity, and often couldn’t even quote their own essays after a few minutes. When writing manually in the final test, they still underperformed.

The authors are careful to point out that the study has not yet been peer-reviewed. It was limited in scope, focused on essay writing, not any other cognitive activity. And the EEG, while fascinating, is better at measuring overall trends than pinpointing exact brain functions. Despite all these caveats, the message most people would take away is that using AI might make you dumber.

But I would reframe that to consider if maybe AI isn’t dumbing us down so much as letting us opt out of thinking. Perhaps the issue isn’t the tool, but how we’re using it.

AI brains

If you use AI, think about how you used it. Did you get it to write a letter, or maybe brainstorm some ideas? Did it replace your thinking, or support it? There’s a huge difference between outsourcing an essay and using an AI to help organize a messy idea.

Part of the issue is that “AI” as we refer to it is not literally intelligent, just a very sophisticated parrot with an enormous library in its memory. But this study didn’t ask participants to reflect on that distinction.

The LLM-using group was encouraged to use the AI as they saw fit, which probably didn’t mean thoughtful and judicious use, just copying without reading, and that’s why context matters.

Because the “cognitive cost” of AI may be tied less to its presence and more to its purpose. If I use AI to rewrite a boilerplate email, I’m not diminishing my intelligence. Instead, I’m freeing up bandwidth for things that actually require my thinking and creativity, such as coming up with this idea for an article or planning my weekend.

Sure, if I use AI to generate ideas I never bother to understand or engage with, then my brain probably takes a nap, but if I use it to streamline tedious chores, I have more brainpower for when it matters.

Think about it like this. When I was growing up, I had dozens of phone numbers, addresses, birthdays, and other details of my friends and family memorized. I had most of it written down somewhere, but I rarely needed to consult it for those I was closest to. But I haven’t memorized a number in almost a decade.

I don’t even know my own landline number by heart. Is that a sign I’m getting dumber, or just evidence I’ve had a cell phone for a long time and stopped needing to remember them?

We’ve offloaded certain kinds of recall to our devices, which lets us focus on different types of thinking. The skill isn’t memorizing, it’s knowing how to find, filter, and apply information when we need it. It’s sometimes referred to as “extelligence,” but really it’s just applying brain power to where it’s needed.

That’s not to say memory doesn’t matter anymore. But the emphasis has changed. Just like we don’t make students practice long division by hand once they understand the concept, we may one day decide that it’s more important to know what a good form letter looks like and how to prompt an AI to write one than to draft it line by line from scratch.

Humans are always redefining intelligence. There are a lot of ways to be smart, and knowing how to use tools and technology is one important measure of smarts. At one point, being smart meant knowing how to knap flint, make Latin declensions or working a slide rule.

Today, it might mean being able to collaborate with machines without letting them do all the thinking for you. Different tools prioritize different cognitive skills. And every time a new tool comes along, some people panic that it will ruin us or replace us.

The printing press. The calculator. The internet. All were accused of making people lazy thinkers. All turned out to be a great boon to civilization (well, the jury is still out on the internet).

With AI in the mix, we’re probably leaning harder into synthesis, discernment, and emotional intelligence – the human parts of being human. We don’t need the kind of scribes who are only good at writing down what people say; we need people who know how to ask better questions.

Knowing when to trust a model and when to double-check. It means turning a tool that’s capable of doing the work into an asset that helps you do it better.

But none of it works if you treat the AI like a vending machine for intelligence. Punch in a prompt, wait for brilliance to fall out? No, that’s not how it works. And if that’s all you do with it, you aren’t getting dumber, you just never learned how to stay in touch with your own thoughts.

In the study, the LLM group’s lower essay ownership wasn’t just about memory. It was about engagement. They didn’t feel connected to what they wrote because they weren’t the ones doing the writing. That’s not about AI. That’s about using a tool to skip the hard part, which means skipping the learning.

The study is important, though. It reminds us that tools shape thinking. It nudges us if we are using AI tools to expand our brains or to avoid using them. But to claim AI use makes people less intelligent is like saying calculators made us bad at math. If we want to keep our brains sharp, maybe the answer isn’t to avoid AI but to be thoughtful about using it.

The future isn’t human brains versus AI. It’s about humans who know how to think with AI and any other tool, and avoiding becoming someone who doesn’t bother thinking at all. And that’s a test I’d still like to pass.